Prior to US entering the WWII, the War

Department had been injecting funds into strategic suppliers.

A major addition to the new Collins “Main Plant” on 35th

street in Cedar Rapids was built with such funds, and the

company was still in the process of occupying the new building

during the weekend of December 7, 1941. Ben Stearns has

documented that Art Collins and the team were busy the weekend

of December 6th and 7th preparing the radio for a meeting with

the Navy in Washington that had been scheduled for December

8th. ART-13s were soon rolling

off those Main Plant production lines. Eventually, more

than 90,000 ART-13s were built by Collins and several other

licensees and many of these radios saw military service into

the 1960s.

The technical advances of the ART-13 were

due to the an elegant marriage of superior electronic design

coupled with precision advances in mechanical and

electromechanical innovations.

Specifically:

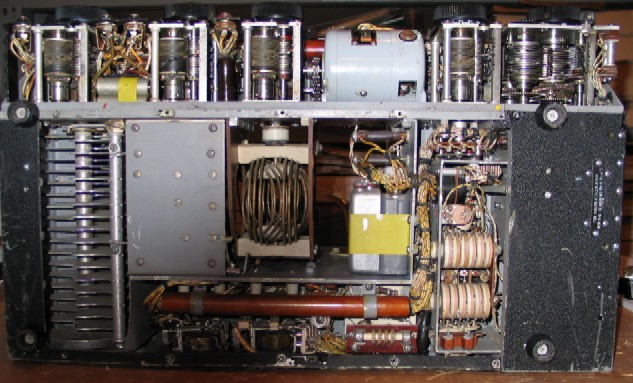

The five autotunes of the ART-13 shown from below. The

single transversely mounted motor in the middle drives all five

autotune mechanisms.

The PTO (Permeability Tuned Oscillator) is on far-right autotune,

and makes 20 full revolutions from stop to stop.

The ART-13 was the first Collins radio to use the PTO, but not the

first to use the autotune.

The amazing autotune assembly.

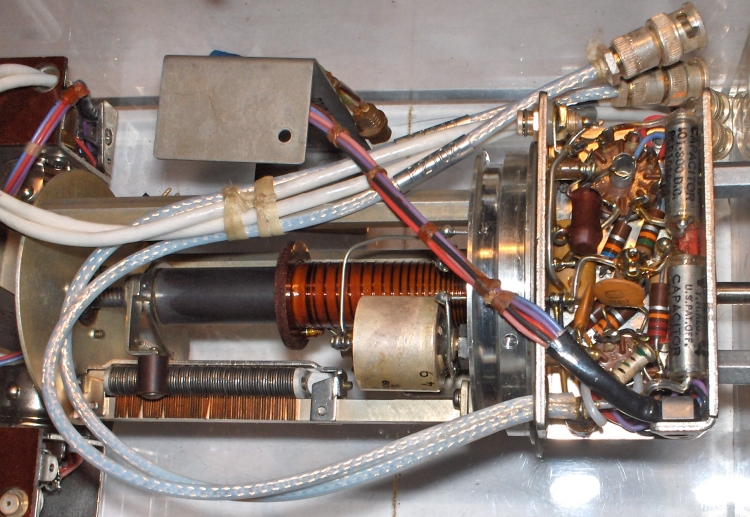

A PTO Assembly. Note the logarithmic spacing of the col

windings on the red cylinder in the center.

The PTO, invented at Collins under the leadership of Ted Hunter,

was first introduced on the ART-13 and quickly

became the standard in linear tuning devices until frequency

synthesizing circuits became practical decades later.

Ted Hunter with a PTO.

Ted Hunter with an ART-13 undergoing tests in an environmental

chamber.

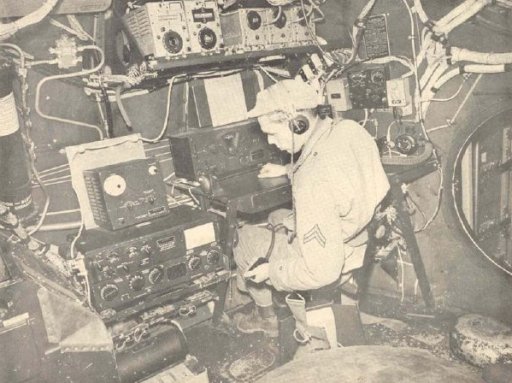

Radio operator and historian Jim B. Smith remembers this experience:

I sat down in my swivel seat, and studied the

equipment. It was all familiar to me except the new Collins'

transmitter. Instead of having to change coils for certain

frequencies as we did in radio school (the radio operators had

to change frequency coils on B-17's and some early B-29's),

these B-29's featured the new Collins' transmitter which gave

the radio operator the capability of presetting 10 frequencies.

Thankfully the Collins made the changing of coils a thing of the

past. This new sophisticated transmitter was made in Cedar

Rapids, Iowa and the radio guys were calling it the "Maytag". (I

liked the idea that it was made in my home state where quality

had always been the hallmark.) As you punched in one frequency

after another, all the dials spun one way, and then the other

until the selected frequency was set up and the antenna loading

was completed. That was the "Maytag" part. It was a wonderful,

time-saving, innovative piece of equipment and featured 75 watts

of power. It transmitted carrier wave (CW), and of course

modulated carrier wave for voice transmissions. There was a

trailing antenna that could be let out when low frequency, long

distance communication was required.

Clyde Hussey remembers it this way:

It was an “autotune” rig . . . just select the frequency you wanted and it automatically tuned the buffer, final and the antenna . . . the knobs whirled and we just watched in awe as it did its thing. It was a FINE rig compared to anything of that day, but a wonder compared to the monster we had in the B-17s and other aircraft we trained in. Those were a real problem to change frequency . . . replace a huge plug-in tuning unit and do lots of manual dial twisting and hope it came out all right. Not very practical in an emergency.

A few of us from the Collins Amateur Radio Club (CARC) thought it would be a great idea to try to recreate a Boeing B-29 Radio Operator position for our local history museum, the Carl and Mary Koehler History Center. Lee Johnson, WT0D, James Jones, W0NKN, Jules Yoder KW0Y, Rod Blocksome K0DAS, H.T. “Tom” Hauer K0YA, all of CARC helped to bring phase one of the exhibit to life. Jules is a consummate craftsman/engineer, and is our team’s official ART-13 expert. He has the perfect resume for this assignment, having serviced ART-13s as a technician in Germany during the Berlin Airlift. My name is Lawrence Robinson, KC0ODK, and I had the privilege of helping coordinate this outstanding team of volunteers.

Along the way we met Mike Hanz, KC4TOS, avionics consultant to the National Air and Space Museum on the famous B-29, Enola Gay. Mike is a walking Army Air Force radio encyclopedia, and has been extremely patient answering dozens (hundreds?) of questions. Mike has also helped us by fabricating and scrounging parts, in some cases donating time and material. Mike introduced us to Steve Williams, KB4DMF. Steve is building the SCR-274N command set for phase two of the exhibit, and has donated hundreds of hours toward this project, donating more time and energy than any other team member.

We also met some people who were there, including B-29 Mechanic Maynard Wege, and B-29 radio operators Jim B. Smith, and Clyde Hussey (KM4RC), all from the 315th Bomb Group on Guam during the summer of 1945. These gentlemen have provided wonderful inspiration and moral support the the project.

Our friend Clyde Hussey shares an interesting ham radio connection of the B-29 story:

After the war was over and while I was still on Guam, I moonlight requisitioned a Collins transmitter and a BC-348 from the Navy (actually, I removed it from a plane parked on the ramp at the Navy field on the south end of Guam) and set up a ham station in an old crew chiefs shack back on Northwest Field. A friendly crew chief got an APU for me and I put it down in a ditch off to the side of the ramp where the shack was. That minimized the noise it made when running. I rigged a phased rhombic antenna for 20 meters and with the help of my crew chief friend, strung it up over the shack and PRESTO, we were on the air. It was not legal at that time (amateur radio transmissions had been shut down during the war - ed.) for the and yet there were some hams operating in the states and we were able to talk to them. I kept trying to contact my dad, but he was too honest to operate illegally, or scared he would lose his license, so we never got in touch directly, but one of the hams I contacted did call him and let him know I was OK and waiting to come home.McArthur’s headquarters in Manila had a communications section that was supposed to keep everybody honest and orderly. They acted as the military FCC. The officer in charge was a good guy. He would give us a call when we were on the air for more than a few minutes and say “You know that is illegal!” Then in the next breath, he would say” If you change frequency it will probably take me an hour or so to find you again.” We did, and he did, and that went on the whole time we were on the air.There was no cold beer on Northwest field, or, so far as we knew, nowhere on Guam. The ham station provided it for us. One of my stateside contacts had a son on Guam and asked me to locate him. I found him in the Navy liquid oxygen plant. When be came up to Northwest field to talk to his folks, the back seat of his jeep always carried a washtub ful1 of beer that was covered in liquid oxygen. As my ham station was responsible for that treat, I had NO trouble getting cooperation from anyone when I needed something to keep the station on the air.

I finally was assigned to a crew to bring a war weary B-24 back to the states, We had a few more discharge points than the poor souls assigned to a troop ship, so that was our ticket to an air trip home. There was no one to take over the ham station, so it was just left there. I have no idea what might have happened to it.